What follows is the transcript of the audio above, an exegetical account of Sartre’s section “The Look” from Being and Nothingness. Sartre explains how our encounter with the Other challenges our own sense of self and our dominion over our world. This is Sartre’s rewriting and reimagining of Hegel’s Master/Slave dialectic, and is meant to show how our subjectivity is constituted in and through an intersubjective encounter with the Other.

Sartre considered himself a writer first and foremost. In fact, he cited his love for writing as one of the reasons why he couldn’t devote himself to a human other in marriage; specifically, he would say that writing would always come first for him and therefore he was not fit for that type of relationship. He took his writing pretty seriously.

What reads, in a lot of Being and Nothingness, and particularly the piece we’re looking at in “The Look,” as rambling, right? It doesn’t feel like there’s structure there, but once you step back and you start to look at it, the structure is actually pretty rigorous. When you think about it, Sartre gives us two examples of seeing the other before he turns that look on himself and you get the chief example of seeing being seen, which is The Look. Today we’re going to go through a summary that will hopefully reveal some of the underlying structure.

Seeing the Other

First, Sartre gives us a couple of examples of the way in which others appear to us as if they were objects, that is, we treat them as if they were objects, which they are not, but we just see people in our environment, they’re walking around doing their own thing, we’re doing our own thing, no problem, right?

But Sartre explains that this is not actually the case, if we reflect on it. That is when we’re walking around and we hear someone talking, we don’t assume, naturally, that this is a phonograph, as he puts it, a record, or a recorded sound. Our first assumption is that this is another person speaking. Indeed, it would be strange if it were not. That would be the exception. The other example he gives us is if we see someone walking down the street, we don’t assume that this is a robot. In fact, we presume that this is another person. So actually our presumption is that others are there, not as objects. But then the question becomes what is exactly the difference between thinking of something as an object versus thinking of it as a subject?

The answer to this has to do with space and time. So the other, a subject, will exhibit a kind of spatiality that Sartre calls distanceless, a distanceless spatiality. And the other will also exhibit temporality, which objects do not do. Sartre would use the phrase the present presence in order to indicate the being of subjects in the world as they are normally encountered. Now, what does this actually mean, in fact? Let’s take a look at the two examples because he explains it by way of the two examples that he gives us.

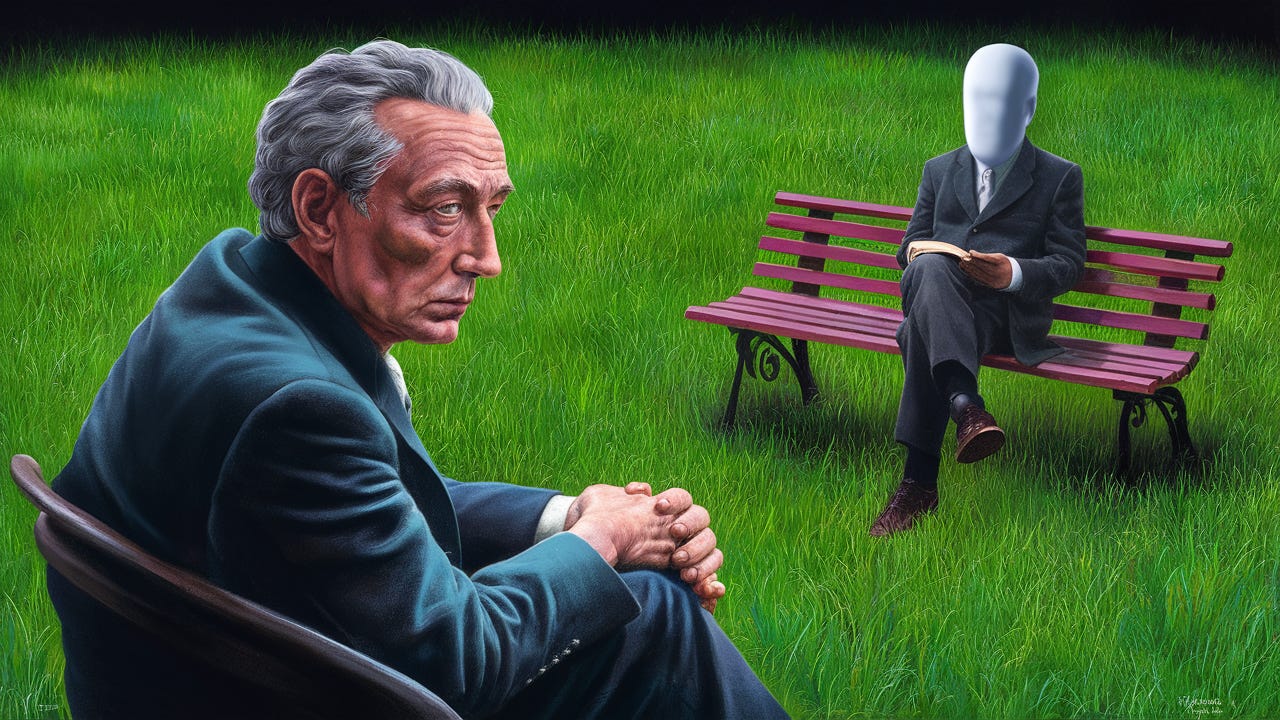

First we have Sartre walking around in a park and he comes across another who is walking in front of a bench across the way a little bit, right? So we’re watching someone else in the park. Now Sartre tells us that the other exhibits a distanceless spatiality to things. Their relation to the things around them is such that they are absorbed in their world. So they might pick up an object and interact with it. Objects don’t do that. That is, objects maintain their distance to each other. The cup that’s on the table next to a chair, the chair doesn’t care about the cup, doesn’t care about the table, and if you were to remove one of these objects the relations of distance of objective distance between them would not change well the relationship between a subject that exhibits present presence and its things is one of physical distance for sure so there is that objective physical distance but there’s also the distance that is manifest in whether one is absorbed, or treats that thing with indifference.

So for Sartre, when the other exhibits this kind of distanceless spatiality, that is the ability to cross distance and become absorbed in things, that alters our own relationship to things. Because the world that had appeared to us as being there objectively, but organized around our own perspective and therefore us now exists for another. So that bench is there and available for the other to sit in. The world appears to them from a perspective that is, by definition, not available to us.

The example that he gives us of this is how the green of the grass presents a face to the other that is not accessible to us. We can objectively say what the color green is. We can say how long the grass is, right? We can say many things objectively about the grass, but the experience of that green, of that grass for the other is something that we fundamentally cannot access because we are not present in their presence. This is what Sartre says, the green turns towards the other, a face which escapes me.

In this example, we are looking at another who is in the world. But what happens if the other is completely absorbed in their world and has no regard for us? Sartre will tell us with his next example that it doesn’t matter whether the other engages with you or not to alter your world. The other doesn’t need to engage with you in order to alter the structure of the world for you. Even if the other were walking around totally absorbed in a book, which is the example we next get from Sartre, where they’re not seeing the grass and they’re not sitting on the bench, their relationship to these things is still there.

So it doesn’t matter whether the other actually uses the object or actually interacts with his world, merely being absorbed in a book walking around, you seeing them already changes structurally your consciousness, because you move from consciousness to self-consciousness. This is something that becomes a little more apparent, perhaps later on in this piece, but it is that reflection of the other’s existence that gets reflected back to us into our interiority, that creates the possibility for self-consciousness. And this is a structural element of subjectivity. This leads later on to the paradox of subjectivity, which we will talk about in just a little bit.

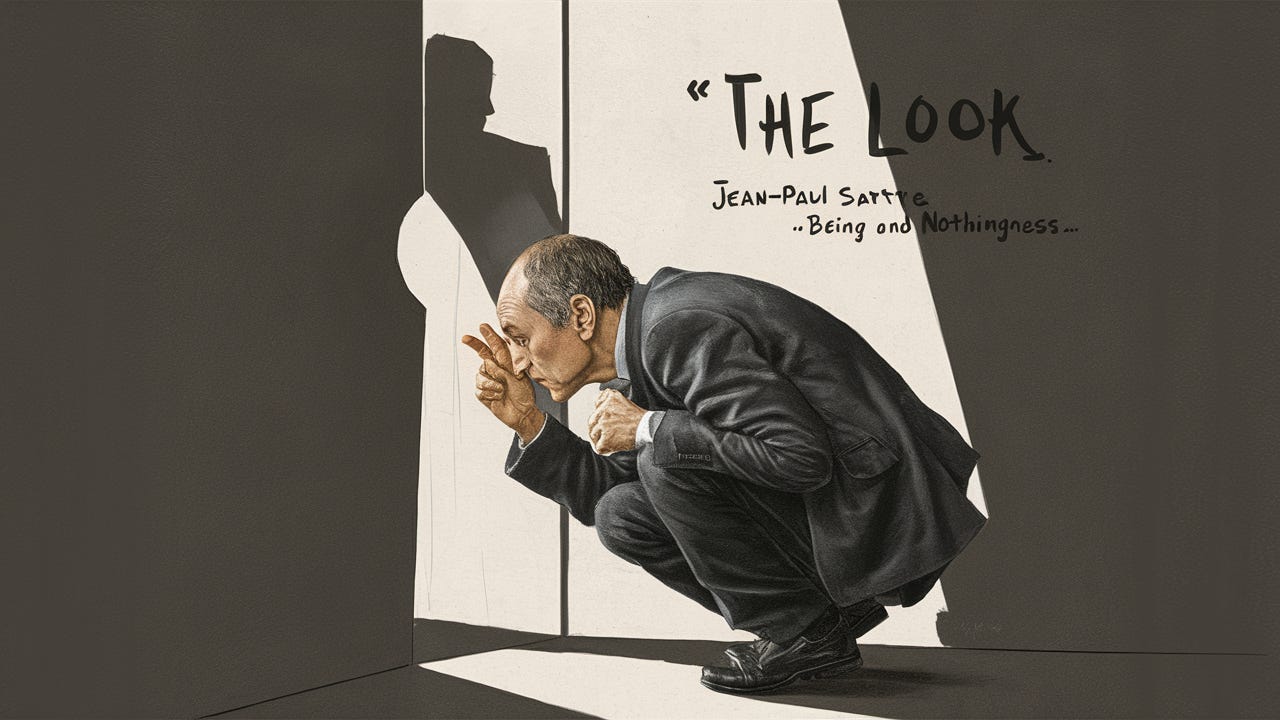

Seeing Them Seeing You, Peeping Voyeuristically Through A Keyhole

Now both of these examples are really prequels to his explanation of The Look. In these previous examples, we are seeing the other, but we actually need to look at this phenomena from the other perspective of seeing the other, seeing you. This is what constitutes The Look. It’s that reflexivity that really creates the phenomena that Sartre wants to explain.

The famous example of The Look is that of a character, a hero, Sartre, who crouches down to peep through a keyhole. And he says that he is driven by jealousy, curiosity, or vice. And that vice would be, of course, voyeurism. So he is doing this without really reflecting on what it is that he’s doing. He’s driven by his desire to fulfill his curiosity or to investigate based on his jealousy or because he’s a voyeur or he has voyeuristic tendencies, right? So driven by this, he crouches down and he’s peeping through a keyhole when he hears footsteps behind him. And he realizes, I think he even turns around and he realizes that he is being seen by another.

And that seeing the being seen is what creates the relation between the self and the other. That is an encounter with the other and not simply a perception or an apprehension of the other in the world. Normally, we reserve the word perceive for objects, we perceive objects, we apprehend Others. And then we have also encounters with others. To get to the level of encountering the other, you need to have The exchanged look, the seeing the other who’s seeing you and when this happens an infinity opens up because it’s like placing two mirrors in front of each other. You see the other seeing you seeing them, seeing you, seeing them, seeing you, right?

And so infinity opens up, and the world appears very differently now, because within this structure of limit of the world, you have the structure of infinity. That’s precisely what the being is for Dasein, that is Heidegger’s description of temporality. This is a reference structurally to something that we haven’t necessarily looked at, but if you’re familiar with Heidegger, that might resonate for you in that way.

What The Look is Not

Now, let’s step back just a little bit because before he actually gives us the voyeurism example, he gives us a little bit of information about what The Look is not as a way of telling us what The Look actually is. The Look is not simply looking at somebody’s eyes because there’s a way of looking at another that objectifies them, that treats them as an object. And Sartre’s example of this is when you look into somebody’s eyes, and you notice their eye color, you might comment on their eye color, right? You’re not seeing them as a person, you’re seeing their eyes as objects. And in fact, there’s a gestalt shift that happens there, where you perceive them, and the eye color that is there, and you look past the person. I think we’ve all had that experience of kind of shifting back and forth between seeing someone as an object and then seeing them as subjects. So I think that’s just one example of that.

Okay, a little aside here. As a thought experiment, the next time that you are looking at someone, be they a beloved or a stranger on the train, try to purposely switch between looking at them as an object and looking at them as a subject, so that you can feel the difference between those two ways of looking. Now, Take an object and see if you can’t train the look on that object. Imagine or try to switch from looking at that object, objectifying it, and treating it as a subject or looking at it as a subject. What happens? What happens when you do that? Just curious. Let me know in the comments.

Okay, let’s return now to the example of The Look.

Existential Shame: the Other Challenges our Autonomy and Delimits our Freedom

The point that we got at in the story is Sartre has been caught in the act of peeping through a keyhole by another and the realization arouses in him shame. Now, shame in this case, according to Sartre, is not what we colloquially would term shame. It’s an existential shame. It has to do with being seen by another and seeing, that leads the realization that the world as we perceive it is no longer ours, and that is a delimiting and a challenge to our autonomy, our sense of autonomy, and autonomy is tied to freedom. So the other challenges our autonomy and delimits our freedom. And this makes us feel ashamed.

In his shame, Sartre looks quickly for somewhere to hide, and he identifies this dark corner. And he thinks maybe if I hide in that dark corner from the other, I will no longer be seen. But the other, who may anticipate that Sartre is going to hide in the corner, forestalls this plan by shining a flashlight, shining a light in the dark corner. So this is an example of the way that the other can outstrip my possibilities, in my being Sartre, right? Sartre judges that given his shame, his set of possibilities are colored by that shame, right? He sees it is possible to hide in this corner, the shadowy corner. The other sees this as possibilities for Sartre and trumps them, forestalls them by shining a light. Now Sartre is in a position of understanding that the other’s possibilities for forestalling his possibilities are such that the other could shine a flashlight and could therefore think of a different set of possibilities I don’t know, running away. And at this point, the other pulls a gun on Sartre and Sartre is caught at gunpoint, and that is it.

The Paradox of Subjectivity

Let me just identify this quickly. There’s a paradox built into this idea of subjectivity here because self consciousness emerges through an encounter with the other. That is, without others, there’s no self. Without consciousness of the other, there’s no consciousness of the self. Therefore, it’s in the very same moment that the subject is born, let’s say, that the subject emerges as reflective consciousness, as autonomous, being able to judge and make decisions, and as free to exert their will in the world. The very moment where that emerges is also the very moment in which that freedom is limited by the other.

So the other that makes the subject possible is also the other through which the subject is threatened in its very existence. This is fundamentally why Sartre will say that hell is other people. This is a famous line from Sartre’s play No Exit. The play tells of a love triangle where X is in love with Y, and Y is in love with Z, and Z is in love with X. So there is this love triangle that kind of illustrates the way in which the mismatching of our affection or intentions are perfectly matched, right? This is a romantic nihilism, let’s say.

But more importantly, you really see this back and forth between my set of possibilities, and the way that that set of possibilities is shaped by how the other apprehends and reacts, or acts, in the face of those possibilities. So other people are hell because others make us who we are, our identity is possible, but at the same time, our very identities are challenged in and through the mere existence of others, others who are unlike us, and who, because of their alterity or their Otherness, can bring us to our heels.

Other people are hell because without the other, we would not have the opportunity for self reflection and we would not be able to know who we are. But the other also represents a delimitation of my freedom and my transcendence as a subject. We don’t know ourselves as transcendent or free until it is reflected back to us in the face of the other, who immediately robs us of that very transcendence and freedom.

Pride

This is the situation in which we find ourselves, existentially. We find ourselves in another, in and through another, who immediately frustrates our desires. This causes us anxiety and much shame and it’s on the basis of this existential shame that pride is possible. Whereas we think that shame is the lack of pride, Sartre would want to claim that it’s the other way around, that shame is the existential mood or attitude, and that pride is simply a negation of that shame. There’s no one more prideful than those who have been shamed. To use continental philosophy lingo, an encounter with an Other is a condition for the possibility of the self, of selfhood, of being a subject. If there’s no other, there is no self. But with the other, the for itself subject, and that’s Sartre’s terminology, the subject appears or emerges under erasure.

Instrument and Obstacle

Now a little bit about instrument and obstacle. This is my favorite part of this whole account. It’s not the peeping-through-the-keyhole, titillating aspect of the story that interests me. It’s actually the instrument and obstacle, the duality of that as it’s presented by Sartre.

I’m going to read two quotes: “The door, the keyhole are at once both instruments and obstacles. They are presented as to be handled with care. The keyhole is given as to be looked through close by and a little to one side, etc. Hence from this moment, I do what I have to do” (p.259).

Now he repeats this kind of language on page 264, where he writes: “My possibility of hiding in the corner becomes the fact that the other can surpass it towards his possibility of pulling me out of concealment, of identifying me, of arresting me. For the other, my possibility is at once an obstacle and a means, as all instruments are. It is an obstacle for it will compel him to certain new acts to advance towards me to turn on his flashlight. It is a means for once I am discovered in this cul de sac, I am caught. In other words, every act performed against the other can on principle be, for the other, an instrument which will serve him against me.”

I love that sentence, and it’s not particularly poetic, but I think there’s a lot of truth in it, so I’m going to repeat it: “In other words, every act performed against the other can on principle be, for the other, an instrument which will serve him against me.” Any instrument, be it a physical thing like a door with a peephole that presents the possibility for spying on what lies beyond it.

A set of possibilities or intentions, as in the case above, are represented as ways of achieving a desired goal — to satisfy our voyeurism, our jealousy, our curiosity, or to satisfy our need in our shame to hide from the other. But these same instruments can turn into obstacles on a dime. The Other ascertains and preempts my hiding in a shadowy corner. The keyhole forces me to crouch low and look into it in a particular way that makes my spying possible. But these things, viewed in a different way, are also obstacles to vision. The door hides what is happening on the other side, enabling curiosity, for example. But in the second case, the other turns my own intentions to hide in a dark corner against me, and is able to more readily catch me. My way out becomes the very way in which I get caught. Now, I can anticipate his anticipation, and make pretence of hiding in a corner, and here I am going beyond the Sartre. Alright, I can pretend, knowing that he thinks I’m gonna hide in a corner, I can pretend that I’m gonna go hide in a corner. Let’s say, I grab a pillow, which now magically appears in my scenario here. I grab a pillow and I dress it up so it looks like a human shape, and I put in the corners of the other things that that’s me, and they go there to look for me and it In doing that, it gives me a chance to escape.

But the other can realize that this is my, in my repertoire. And again, transcend my transcendence, as Sartre puts it. Outstrip my possibilities. And think, ha!, that’s not them, that’s a pillow. And go after me. So I think you get the idea here. My set of possibilities are shaped not just by my own sense of who I am or by my autonomy or my freedom, but they’re shaped by the other’s possibilities, by their desire and their need to transcend my transcendence or to outstrip my possibilities.

How Our Relation to the Other Is Always Already Political

So what here is Sartre describing? He’s describing the relation to the other as essentially political in nature. That is, of a relationship between us and them, self and Other, and this makes a special sense when one considers that Sartre was the preeminent political thinker of his time. This was his bailiwick, so he sees the relationship between self and other, between us and them as a political matter. The other is always trying to anticipate and block the ways in which we anticipate and block their anticipation and blocking of us and of our interests.

This also reminds me that for every action, there’s a reaction. You might have, heard that before. I think that’s a saying. So any move by the other must be countered, or else they win. They are strengthened by the lack of countering or resisting their advances on our territory or our freedom. And I think that’s a key, key, key lesson of the resistance to oppression.

One of the key problems, also politically, that is how do those who are oppressed gain power? It’s tricky to describe theoretically, but if we look at history, there are many examples of those who were not empowered and didn’t have the means, rising up and overtaking, say, political power, or economic power, or racial power.

Describing how exactly that happens is really pretty tricky. Every action deserves a reaction. Even if the reaction that you can afford is pretty small, nonetheless, some sort of reaction is necessary in this political game between self and other. This is something that came up for me as I was reading this part of the Sartre because it clicked for me that, ah, okay, this back and forth between the other is the fundamental relationship of the antagonism between self and other, between us and them.

It brought me back to the very beginning of the series where we set up the question of the problem of the Other, of intersubjectivity, as a problem for identity and for political identity. That is how we define us, ourselves, or our group through exclusion, so that the relation between the self and the other, how we construct identities is antagonistic. And Sartre’s very much in the tradition of Hegel, where the relation to the other is fundamentally alienating and threatening to the self. A relation to the other, beyond it being a relation of knowledge, of knowing the other, or it being an ontological matter, which would be Heidegger’s way of approaching it… Sartre here captures the essence of the relation to the other as political.

Seeing and Being Seen Seeing: Sartre’s Voyeuristic Reimagining of Hegel’s Master/Slave Dialectic