Becoming-Feminist

A reading of Sandra Bartky's "Toward a Phenomenology of Feminist Consciousness"

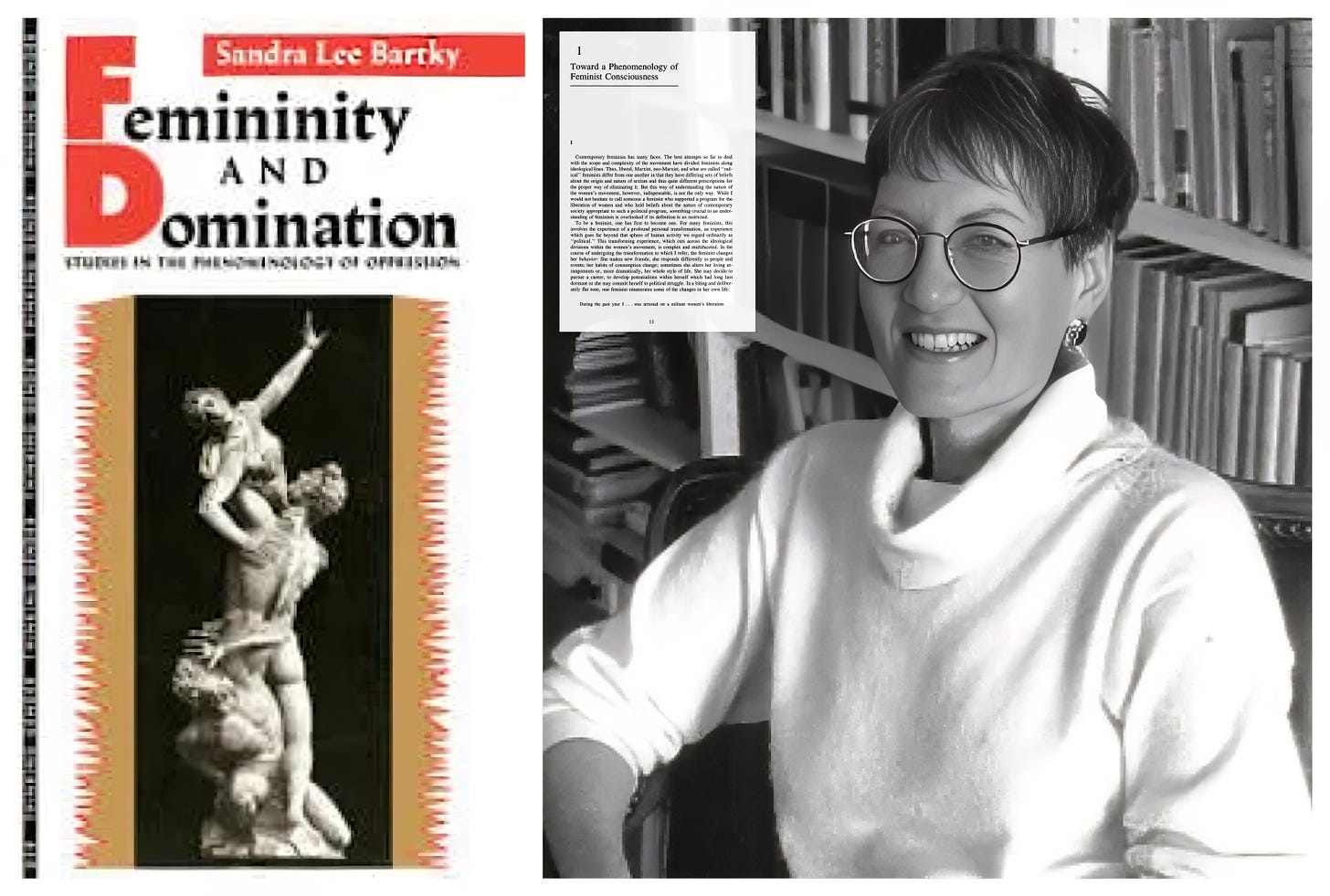

Sandra Lee Bartky would have been 90 years old this year, were she still alive. She passed away in 2016 at the age of 81 in her Michigan home. Her essay, "Toward a Phenomenology of Feminist Consciousness," first published in 1976 (and reprinted in her first book, Femininity and Domination, in 19901) would have been one of the earlier essays in feminist philosophy. In this work, Bartky brings together the Marxist analysis of class-based oppression and a phenomenological interpretation of becoming-feminist — no small feat. Phenomenology is a method that seeks to uncover the structures of subjectivity, in this case the structures for a feminist consciousness.2 How does a woman — and here the focus is on women — become a feminist, what are the conditions for the possibility of becoming-feminist, and how is her subjectivity different from that of the not-yet feminist subject?3

There’s nothing quite like these early attempts to theorize women’s experiences using “the master’s tools."4 Bartky mentions Marx, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Sartre, and Marcuse, but doesn’t spend any time rehearsing their arguments. She just picks up their tools and puts them to use in unintended ways. I appreciate that. There’s also an authentic struggle with language in this essay — of working through the feminist experience in a systematic, philosophical way; trying to whip words like "weariness" into technical terms à la Heidegger; and also there are missteps, like where she seems to argue that what we would today call micro-aggressions are unique to women's experience of oppression.

Undoubtedly, "Toward a Phenomenology of Feminist Consciousness" is a work of its time. Born in 1935, Bartky was technically part of the Silent Generation, though she is on the cusp of the Baby Boomer generation. Her ideas align with the generation who came of age in the late 60s and early 70s, when the second wave of feminism took root alongside other liberation movements -- the Algerian Liberation Front, Black Liberation, Gay Liberation, and Women's Liberation. According to Bartky,

"What triggered feminist consciousness most immediately, no doubt, were the civil rights movement and the peace and student movements of the sixties; while they had other aims as well, the latter movements may also be read as expressions of protest against the growing bureaucratization, depersonalization, and inhumanity of late capitalist society. Women often found themselves forced to take subordinate positions within these movements; it did not take long for them to see the contradiction between the oppression these movements were fighting in the larger society and their own continuing oppression in the life of these movements themselves"(13).

Tipping her hat to Beauvoir and her well known quote that one is not born, but rather becomes a woman, Bartky writes that “To be a feminist, one has first to become one” (11). She will theorize that process of becoming-feminist, starting from an awareness of oneself as a victim of systemic oppression. Women have long resigned themselves to their situation as women, some even seeing it as a natural state of affairs. But when a woman feels herself victimized, she can already see that the way things are are not the way they should be, she begins to envision a different state of affairs as possible and necessary. Bartky warns that this new vision still needs to be grounded in reality, that is, be in the realm of possibility, otherwise it is a delusion. But the line between the possible and the impossible is often hard to make out. Just because Bartky is a realist doesn’t mean we have to be!

“To be a feminist, one has first to become one”

A key idea elaborated by Bartky is that of “double ontological shock.” It appears towards the end of her account, but we will start there and work our way backwards. It captures the confusion and wariness that structures becoming-feminist:

"In sum, feminists suffer what might be called a 'double ontological shock': first, the realization that what is really happening is quite different from what appears to be happening, and, second, the frequent inability to tell what is really happening at all" (17).

In the first turn, the would-be feminist interprets a shared reality differently than a woman whose consciousness has not been awakened.5 She may even seem paranoid to others, where she sees the invisible hand of compulsion and coercion in everyday situations. Her focus may be sharp one moment, and thrown blurry the next. At times she will doubt her own perceptions — which is where being able to get some epistemic validation from others is super important — and her convictions may waver. She may become unsure of herself, even suspicious of herself.

For example, the feminist walking through the toy store notices the way those toys are gendered and recognizes it as gender normativity at work. (The non-feminist might see the same thing and think it well and right.) The feminist may see this as an opportunity to mess with gender norms by purposefully ignoring these gendered expectations. Bartky describes wanting to buy a doll for her nephew and an erector set for her niece, and then worrying about the fallout from that choice. It bothers me to this day that she tells us her ultimate choice, which I won’t repeat here so as to not ruin it for my readers. Nonetheless, it is a nice phenomenological description of the experience:

"In a light-hearted mood, I embark upon a Christmas shopping expedition, only to have it turn, as if independent of my will, into an occasion for striking a blow against sexism. On holiday from political struggle and even political principle, I have abandoned myself to the richly sensuous albeit repellantly bourgeois atmosphere of Marshall Field's. I wander about the toy department, looking at chemistry sets and miniature ironing bards. Then, unbidden, the following thought flashes into my head: What if, just this once, I send a doll to my nephew and an erector set to my niece? Will this confirm the growing suspicion in my family that I am a crank? What if the children themselves misunderstand my gesture and covet one another's gifts? Worse, what if the boy believes that I have somehow insulted him? The shopping trip turned occasion for resistance now becomes a test. I will have to answer for this, once it becomes clear that Marshall Field's has not unwittingly switched the labels. My husband will be embarrassed. A didactic role will be thrust upon me, even though I had determined earlier that the situation was not ripe for consciousness-raising. The special ridicule which is reserved for feminists will be heaped upon me at the next family party, all In good fun, of course" (19).

This account goes quite nicely with feminist philosopher and phenomenologist Sarah Ahmed's appropriately named figure of the feministkilljoy. In Living a Feminist Life (2017), Ahmed describes the feminist killjoy as someone who "spoils" the mood by pointing out injustice, exposing uncomfortable truths, and refusing to smooth over conflicts related to sexism, racism, and other forms of oppression. This figure, rather than simply being negative, uses discomfort as a form of resistance, highlighting the contradictions in a society that values happiness over justice. Everywhere, the feminist sees her subjugation, and in the most surprising of places sometimes. But also, the possibility for resistance. It can get quite exhausting, but this is the work.

We have examined how the experience of becoming-feminist is characterized by confusion — confusion due to the ontological shock at a shape-shifting reality. "Wariness,” on the other hand, “is anticipation of the possibility of attack, of affront or insult, of disparagement, ridicule, or the hurting blindness of others. It is a mode of experience which anticipates experience in a certain way; it is an apprehension of the inherently threatening character of established society. While it is primarily the established order of things of which the feminist is wary, she is wary of herself, too" (18-19). She may second guess herself, and become suspicious of her own motives.

"In sum, feminist consciousness is the consciousness of a being radically alienated from her world and often divided against herself, a being who sees herself as victim and whose victimization determines her being-in-the-world as resistance, wariness, and suspicion."

Near the end of the essay, perhaps realizing how unpleasant the feminist experience sounds, Bartky includes some final thoughts on liberation. Talk about burying the lead!

Let’s start again there. Seeing oneself as a victim, which is the beginning point for becoming-feminist, can be redescribed as courageous. Courageous because this feeling exposes us to our base vulnerability to others, and to identify with that vulnerability is already courageous. The women who see women’s oppression as natural fear their human vulnerability, and disavow their own humanity. Also, let’s add the idea that feminist consciousness is a shared subjectivity. While it manifests in the experience of an individual, its emergence as such is only possible within the context of a larger group identity (“feminist”), itself a collectivity of shared story-telling. You don’t become a feminist all by yourself, you don’t learn to look slant at normative “reality” with no support. Feminists do not fall out from coconut trees, after all.

Feminist consciousness is a consciousness of one’s victimization set against a horizon of liberatory politics, a shrewd idealism, and a nearly delusional hope for the future. There is no consciousness of being victimized without an idea of injustice; no idea of injustice without justice; and no idea of justice without idealism. Our victimization as part of an underclass of women, in the context of a misogynist culture and patriarchal institutions, is not acceptable. We can say that with our whole mouths.

Realizing one’s victimization as such gives one access to beginning to understand other forms of oppression, the logics of which are the same in spite of different histories and material realities. This awareness is not a passive acceptance of victimhood, it is not something we have to take on and carry, but is rather a burden that can be shifted onto those who benefit from injustice. It is their burden to carry and to unpack.

To be continued…

Footnotes

It was part of the Thinking Gender series edited by Linda Nicholson and put out by Routledge that defined a whole generation of feminist philosophy, and included Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble and Andrea Nye’s Words of Power.

For an introduction to Phenomenology, you can read my primer here:

I was trying to articulate what transformations we undergo by studying philosophy and feminist philosophy when I remembered this piece, because it quite directly speaks to transformations. Bartky chooses a pretty dramatic example to illustrate: "During the past year I . . . was arrested on a militant women's liberation action, spent some time in jail, stopped wearing makeup and shaving my legs, started learning Karate and changed my politics completely" (11-12).

This is Audre Lorde’s turn of phrase in “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, Crossing Press, 1984, pp. 110-113.

The feminist, Bartky writes, doesn't see different things, but sees things differently. "Feminists are no more aware of different things than other people; they are aware of the same things differently" (14).

“Picks up the tools uses them in an unexpected way” … I love that